|

Intermix.org.uk is a website for the benefit

of mixed-race families, individuals and anyone who feels they have a multiracial

identity and want to join us. Our mission is to offer a view of the mixed-race experience, highlighting icons, film, books, poetry, parenting techniques, celebrities, real lives and much more. Our online forums are a great place to meet others, ask questions, voice your opinions and keep in touch. Sign up for our monthly newsletter and delve into our pages. Want to join in? Become an Intermix member to take part: |

London River

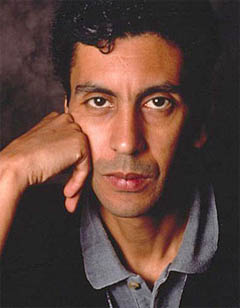

Director Rachid Bouchareb talks about his involvement in London River

Issues of race, nationhood, community and kinship lie at the heart of your films. What were your specific motivations for making London River?

‘I would say that all my films are concerned with the subject of meetings between different people, from different countries and different worlds. This theme of meetings is always at the heart of my films, because the characters are always on a journey. And this phenomenon goes beyond the characters on screen to the actors themselves. I find the concept of the meeting between Sotigui Kouyaté, an African actor, and Brenda Blethyn, a British actor fascinating – beyond the fact of their friendship, it’s a human connection between two people of different nationalities, religions, universes. It allows one to go beyond the cinematic encounter and affords the film a level of truth about the meeting and the different cultures of these two individuals.’

Did you always have Sotigui & Brenda in mind for the parts?

‘Sotigui, yes. After we made Little Senegal together, I knew I wanted to work with him again, and I wrote London River with him in mind. As for Brenda, I’ve had her in mind for something ever since I saw Mike Leigh’s film Secrets & Lies . When I finally met her she was very busy working on other projects, so I waited a year for her to be free, because I knew it had to be those two for the film. They were the film.’

You’ve said in an interview that the subjects you choose to film allow you to find yourself. Did you find yourself within London River?

‘In as much as this is a film about the problem of being a Muslim in Europe, then yes, this film concerns me personally. I was living in France at the time of the World Trade Centre attacks, and I felt the after-effects. Suddenly it was more difficult than ever to be an Algerian in France.’

How were the bombings perceived in France at the time?

‘I’d compare it to the impact of the Madrid bombings in France. Really, there wasn’t much coverage in the press, and I’d say that the attitude of the French population at that time was... well, I didn’t hear people talking about the attacks like I did after 9/11, not with the same sense of urgency. It was as if after the initial crisis, that is, the World Trade Center attacks, nothing could be as shocking. Nothing that came afterwards could have the same effect.’

The subject matter is quite sensitive...

‘I hope that people who see the film will understand that the event itself is just starting a point. My film is less about the bombings themselves, and more about the meeting between these two people that takes place in their wake. That’s what was important to me, that these two people who meet are united by the same problem, which is their desire to find their children. And the story is about these two people, a man and a woman from very different backgrounds but faced with the same fears, the same anxieties. It needed a crisis to bring them together, but that crisis could have been something else, the September 11 attacks for example.’

‘London River is first and foremost a human drama, about how people react to events such as these, how they come together in the same place and forge a connection. Events such as the attacks of 7/7 naturally divide people, but at the same time they also bring them together. They need one another. People have to come together in the face of such crises. It’s an obligation.’

What research did you do for the film?

‘The coverage we see of these events on our televisions is already very strong, we don’t need to add to it, but to give these dramas a human face. Although the film contains archive footage of the events and their real life victims, I didn’t do a lot of research into the impact of the attacks on the people that lived through them – interviews with families affected and so forth. Rather I was interested in taking these two actors, living with them, seeing how they would approach their characters and what relationship would develop between them: their encounter. This is what lends the film its universality. Whether I had made the film with Chinese actors, Indians, Arabs, or actors from other parts of Europe, it would have been the same, concerned with these same fears, worries, dramas.’

‘I didn’t want to have to stick to the historical facts and eyewitness accounts – these things are there in the film, on the televisions we see on screen. But for the story I wanted to go beyond that, to find something deeper.’

How did you go about writing the screenplay?

‘I wrote the story for the film before we started shooting, but once we started there was some improvisation: the scenes were all there, but there were gaps that needed filling. So when Brenda’s character first arrives outside the Butcher’s shop that her daughter lives above, for example, or when she first encounters Mr Ousmane her response in these scenes wasn’t scripted, the gestures were completely spontaneous.’

‘There was more improvisation still at the level of the two leads, scenes that weren’t written in advance. For example when we see them sharing an apple, or their characters’ final parting. I couldn’t have scripted the physicality of that embrace they share, when he holds himself strong and straight like a tree, while she clings onto him, just as I couldn’t have scripted the song Sotigui’s character consoles Brenda’s with – that came entirely from him. He felt the need to sing then, so he did. For me, this working method produced some of the most moving moments of the film.’

There’s a beautiful physical contrast between the two actors...

‘Exactly. That’s why I needed those two actors and no-one else. It’s a very important element of the film. In fact, you might say it is the film. The film has a rough, documentary aesthetic, which is quite a contrast from the polish of Indigines... ‘

‘After the precision that Indigines demanded, I wanted complete – absolutely complete – freedom on this film. I wanted to forget cinematic aesthetics entirely, to put aside all technical discussions. All that concerned me was the characters. We had a district of London, two actors, 15 days, and we were working day to day. There was little light, a very small team. Working like this I was free from the obligation to spend a long time preparing scenes, rehearsing, setting up shots. It was very refreshing to work like this, with very little preparation or preamble. In fact, the week before we started shooting I was in Cannes, judging the festival competition, and from there I flew straight to London to begin the film. I didn’t spend weeks in advance thinking about the film; I arrived with a clear head. And as a result both the shoot and, I think, the film, were much more spontaneous and much more intimate.’

Were there any particular cinematic influences on the film?

‘What was great about this film is that I could take myself away from other films, there were no influences, no imprisonments, no obligations. That was important, because as I’ve said, I wanted to be free, I wanted the actors to be free, and I wanted the film to be free. So I didn’t want to have any ‘concepts’ in my head before we started shooting. That’s why it was so important that I arrived on the set in this very calm state. And I think the film is better for that. That said, I feel very strongly that cinema should move you, make you feel something. Always. Indigines did that – at screenings across the country I saw audiences weeping while they watched the film. And that’s important, to produce strong feelings. I like melodrama. ‘

‘I like Gone With The Wind ; Paris, Texas ; Bridge Over The River Kwai . Films like this have a human warmth, they have the power to bring their audiences to tears. And that’s something I aspire to.’

What is the role of faith within the film? Although the first two scenes show the protagonists at prayer, in most other ways, religion seems strangely absent from the film?

‘Quite simply, the two protagonists each live with their own faith serenely. Because one can have faith, and live with it, and be a good person. Just like that. There are plenty of people who have their beliefs. It is part of who they are, but it doesn’t necessarily define them. Politics, faith, nationality – these things aren’t the same. That’s why you have the character of the policeman, who tells Ousmane that he, too, is a Muslim. That is, not all Muslims are Arabs: there are Muslims in China, in Russia, in Eastern Europe. There are Europeans who are Muslims. In France. In London. I wanted to show this. One thing that stands out is the constant failure of connection between people, even between loved ones. Both the protagonists know so little about their children’s lives.’

‘I think the great problem of our times is a lack of communication. You see this in global politic relations. Is there any discussion? Is there any understanding? People don’t talk to one another any more, the world has difficulty doing this. You see it every day on the news. Rarely do we see people sitting round a table for days on ends conversing, talking things through. No. Instead we see people armed, at war. This problem begins at the level of personal relations, and the solution can only start here too.’

In many ways the film seems to be summed up by the line that she speaks, “our lives aren’t so different”.

‘It’s true. Our lives aren’t so different because we’re not so different, whichever of the four corners of the globe we might live in. In our thoughts, our feelings, our fears, our joys, our hopes and worries – our lives, they’re not so different at all. They’re the same.’

There’s a strong juxtaposition between the rural and the urban.

‘I wanted to show the manner in which both of these characters live somehow outside of the world, and to show the futility of this. She lives on her island, he lives in the forest, but one can’t continue like this. One can’t remain completely isolated.’

And yet both characters return to their rural retreats. What are we to make of the film’s ambiguous ending?

‘It’s completely up to the spectator to decide what might happen next. Life goes on. The farm, the forest: these are their homes, their work and their lives. What else would they do but return to them? I think the spectator can draw his conclusion from this ending, by putting himself in the place of these characters.’

London River is available to buy on DVD now.

Win a copy of London River on DVD

Interview with Rachid Bouchareb

Have you seen this film? Why not tell us your views in the forums, click here: