|

Intermix.org.uk is a website for the benefit

of mixed-race families, individuals and anyone who feels they have a multiracial

identity and want to join us. Our mission is to offer a view of the mixed-race experience, highlighting icons, film, books, poetry, parenting techniques, celebrities, real lives and much more. Our online forums are a great place to meet others, ask questions, voice your opinions and keep in touch. Sign up for our monthly newsletter and delve into our pages. Want to join in? Become an Intermix member to take part: |

Blood In The River (part two)

The year I stopped, in my own mind at least, being just an honorary white boy.

The year I stopped, in my own mind at least, being just an honorary white boy.

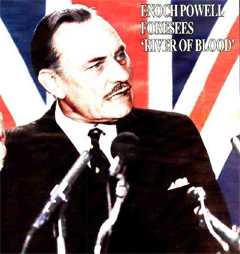

I was eleven years old when the ripples from Enoch Powell’s Birmingham speech in 1968 reached the ears of my family in Devon. By the middle of that summer, there was little else in the way of political debate amongst members of my family and, as I was later to discover, in the rest of the country too.

My grandfather, a long-time Powell supporter, was the head of the family; his financial success, generous spirit, sense of humour and loving nature made him a popular figure wherever he went. With our mysterious father absent, my grandfather was the most influential male in our household for my sister and me, and we loved him. But 1968 was the year I became politicised. It was the year I started to question my identity more fully, it was the year I realised that the racism that I had, by then, begun to recognise at school, wasn’t isolated, wasn’t simply a matter of my peers not liking me; it was political, it was personal, and it hurt. It was also the year I stopped, in my own mind at least, being just an honorary white boy.

Even at eleven, old habits die hard. By June I had turned twelve and felt that, a year away from rampant teenagerdom, I was already worldly. But it was not as easy as I had imagined to cast off my negatively perceived caste and I slipped right back into it as a default mode. My strategy, such as it was, born out of the necessity to survive more than anything, was to remain an honorary white when situations became tricky and to start to assert my identity when it felt safe, which wasn’t very often.

At the start of the Autumn term, the effects of the Powell speech were already evident. The taunts had become more frequent and more aggressive. In English classes, I was chosen to read a passage aloud from a Biggles book; my memory is one of both deep embarrassment, fear and resentment that I should have to read out lines containing the phrases ‘black peril’, ‘slitty-eyed devils’ and ‘foreign hordes’. Thenceforth, I was nicknamed Yellow Peril or Yellow. The name-calling started as a taunt but I mostly managed to avoid confrontation by simply adopting the names as part of my identity, even introducing myself to other children as Yellow Peril. It was humiliating but it was better than an escalation of the beatings and thefts that I had to put up with, on and off, for the duration of my entire education.